Now you see me, now you don’t—a three-part exploration into shifting workplace risk assessments from tangible to intangible hazards.

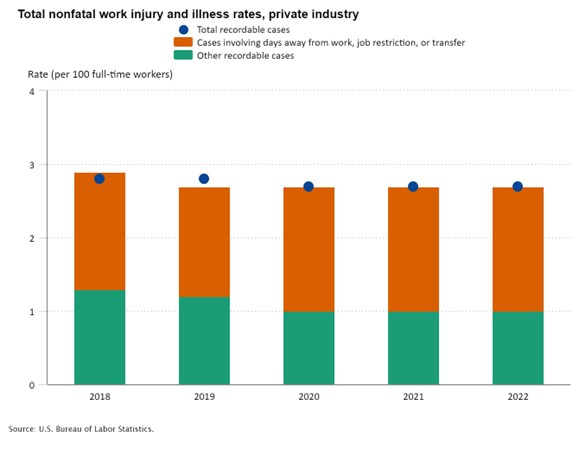

For over 50 years, the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) has focused on ensuring that America’s hard-working men and women can go to work without the worry of being harmed or fatally injured. They have completed this by concentrating on incident inspections and proactively inspecting the physical conditions in the workplace. And let’s be honest, they have done a great job decreasing injuries and fatalities in the workplace, but that progress has stalled over the last decade or two.

As safety professionals, we do not generally take our roles in safety to ensure a company receives the lowest fines from OSHA. We take our roles because, for one reason or another, we become passionate about ensuring employees are exposed to the lowest number of hazards and risks in the workplace and that they can unequivocally feel safe at work from injury or death.

To continue making positive changes year after year, we must evolve, find new perspectives, and identify new sources of hazards previously overlooked. We invite you to join us over the next couple of months as we discuss two of the often-overlooked workplace injury sources: ergonomics and psychosocial risks.

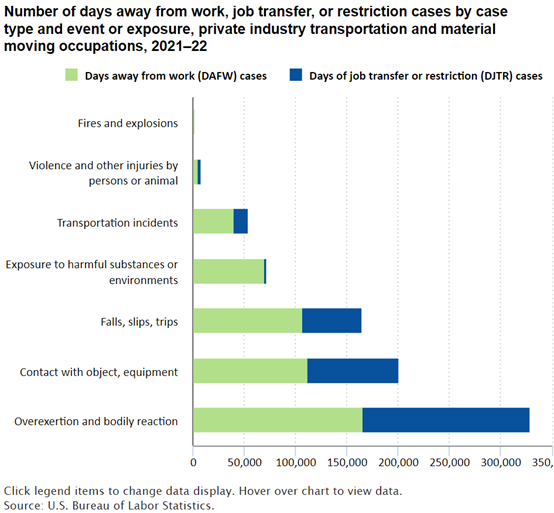

Ergonomics is the study of how employees interact with their environment. In the workplace, this involves examining how that interaction causes injuries, including musculoskeletal injuries. Ergonomics is not a new concept, but OSHA does not have a specific standard addressing it in the workplace. However, OSHA has increasingly cited businesses under the general duty clause for ergonomics-related hazards and injuries. Below, you can see that overexertion and bodily reaction account for the majority of days away from work, job transfers, or restrictions in the workplace. When we dive into ergonomics, we will discuss some of the causes of these injuries, some processes to identify ergonomic risks in your workplace, and how to implement control measures to decrease risk to employees.

Just like ergonomics, assessing workplace psychosocial hazards is not a new concept; however, it is far from being implemented in most businesses. Safety professionals will undoubtedly start to identify and evaluate psychosocial hazards in the workplace as they continue to find new ways to prevent employees from being injured. In September 2024, the University of Washington School of Public Health performed a detailed analysis of psychosocial hazards in the U.S. workforce in 2022.

“Researchers looked at 19 psychosocial hazards, divided into three categories:

- Job demand and control exposures, which includes hazards like highly structured work and repetitive tasks

- Social environment exposures, which includes dealing with unpleasant and aggressive people

- Work schedule and wage exposures, which includes irregular work schedules and long work hours

They found that half of all U.S. workers are exposed to at least three psychosocial hazards in their workplace that could negatively impact their health. Tight deadlines is the most common, with 43% of all U.S. workers exposed, followed by high emotional labor (36%) and low wages (30%).” (Stringer, 2024)

In the psychosocial hazards portion of this series, we will discuss how these hazards potentially impact workplace injuries. Stay tuned; we look forward to continuing this conversation over the next two issues of this newsletter.

Related Posts